19 August 2018

Every day, we hear of yet another reason to get worried about our mental health and about whether or not we are suffering from a mental illness without realising it. The media's covering far more about it than ever before.

Students are under severe stress at our universities, children are suffering stress from social media, and, according to the iPaper (16 August), the hoarders among us have serious reason to start worrying about clutter: ‘Perhaps we’ve watched, fascinated and repulsed, at TV shows such as Britain’s Biggest Hoarders, which feature homes stuffed to the gunwales with, well, stuff...

‘…This week, it was classified as a mental disorder by the World Health Organisation, which explained that “accumulation of possessions results in living spaces becoming cluttered to the point that their use or safety is compromised. The symptoms result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning.” (my italics)

‘…This week, it was classified as a mental disorder by the World Health Organisation, which explained that “accumulation of possessions results in living spaces becoming cluttered to the point that their use or safety is compromised. The symptoms result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning.” (my italics)

Mental Disorders half a century ago

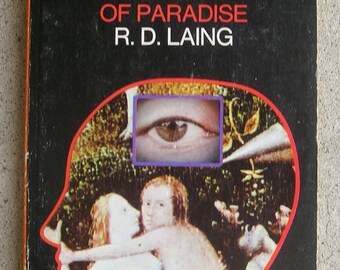

Writers like Erving Goffman and R.D. Laing (1967) were writing books that questioned what were then common definitions of mental health and illness – long before the 1975 film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest or my own 1978 book Discovering Suicide'.

Writers like Erving Goffman and R.D. Laing (1967) were writing books that questioned what were then common definitions of mental health and illness – long before the 1975 film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest or my own 1978 book Discovering Suicide'.What these had in common was that they not only questioned the way mental health and illness were defined, but were also critical of psychiatrists and the way they (and their associated staff) treated and managed patients suffering from the 'illness'.

The medicalisation of social problems

In the 1960s and 1970s, sociologists and others were arguing that using a medical model to define and explain different forms of deviant behaviour (like delinquency, crime, alcoholism, mental illness, suicide, etc.) was a convenient way of defending and preserving the status quo. After all, if these were illnesses, society could hardly be blamed for causing them. So in that sense, medicalisation involved adopting an essentially conservative model of social problems.

Psychiatry was (and still is?) the lowest status of all among medical specialisms

While doing a PhD on suicide in the late 1960s and early 70s, I came into contact with quite a lot of psychiatrists, some of whom were working in mental hospitals, and others working in research units.

What surprised me then (and still surprises me today) was how quickly they became qualified in their chosen specialism: after graduating in medicine, it only took one postgraduate year to qualify in psychiatry - which involved spending relatively little time learning about social and psychological factors compared with time spent learning about what drugs should be used to treat which types of mental illness.

What surprised me then (and still surprises me today) was how quickly they became qualified in their chosen specialism: after graduating in medicine, it only took one postgraduate year to qualify in psychiatry - which involved spending relatively little time learning about social and psychological factors compared with time spent learning about what drugs should be used to treat which types of mental illness.

Perhaps the biggest weakness of psychiatry is that (unlike cardiology, oncology or brain surgery) it lacks a killer disease that its specialists can actually cure.

Other weaknesses will be discussed in later blogs.

Meanwhile, we should take our hats off and acknowledge psychiatry's PR triumph now that the WHO has classified hoarding as a mental disorder...

Subscribe to: Posts (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment