_______________________________________________

Blogging on 20th August, I raised some questions about psychiatry and psychiatrists without saying much about my reasons for doing so - apart from noting that, in the face of growing problems of mental health, it's a 'science' that's regarded with much less scepticism these days than was the case in the 1960s.

This is a true story about someone who was treated by 9 different psychiatrists in 4 years, only three of whom were native-speakers of English.

This is a true story about someone who was treated by 9 different psychiatrists in 4 years, only three of whom were native-speakers of English. Having recently had some blood tests, he went to see his new GP for the results.

As he was worried, after 4 years under so many different psychiatrists, if his official medical records said that he was suffering, as he suspected, from 'vascular dementia'. And, if so, which of the many psychiatrists had mistakenly diagnosed him as suffering from this incurable illness.

Psychiatric provision in a small town and a recovery plan that failed

In charge at the first hospital to which he was admitted, were two ethnic African psychiatrists, neither of whom were fluent speakers of English. After a few months they discharged him and he was treated in accordance with the recovery plan that they'd devised.

This involved being 'treated in the community' by a locus-psychiatrist whose native language was Serbian. His English was very poor, added to which he had a serious hearing (and listening) problem.

At the first meeting, he told the patient and the other family members accompanying him that he'd left his hearing aid in his car.

At the first meeting, he told the patient and the other family members accompanying him that he'd left his hearing aid in his car. But when one of them offered to go to the car park to get it for him, he said he didn't need it because he could lip-read English perfectly well - even though he couldn't actually speak English perfectly well.

The Serbian then sat down facing the family, with his back to the patient. In so far any of them could understand anything he said, he strongly implied that not all the drugs that had been prescribed by the Africans were necessary.

The patient therefore stopped stopped taking some of them and his condition gradually deteriorated.

After seeing the same consultant a few more times, he was sent (against his will) to another mental hospital 25 miles away from home - which was a blessing in disguise.

Psychiatric provision at a hospital in a bigger town and a recovery plan that worked

A notice board in his room at the second mental hospital informed him that his psychiatrist was no longer the Serbian, but a Dr W, whom he had yet to meet and who didn't come to see him for several weeks after he arrived.

Finding out where Dr W was quite a challenge. Some of the nurses said that he was on sabbatical leave somewhere in North America, some that he was on holiday in the USA and others that, as he'd taken early retirement, he could now afford to work when he felt like it.

The most promising news was that he was a native-speaker of English, who everyone agreed, got on well with his patients, was a good chap and a 'good psychiatrist'.

It didn't take Dr W and the nurses long to devise a recovery plan and discharge their patient fairly quickly.

Postcode lottery:

His experience in these two mental hospitals demonstrated that there's a postcode lottery in the treatment of mental illness, just as there's a postcode lottery in the treatment of physical illnesses.

Compared with what happened at the local small town hospital, the effectiveness of the treatment (and aftercare) at the more distant hospital in the bigger town was far superior.

Drugs are much more effective than they were in the 1960s and 1970s:

Although it's not at all clear how they all work, the drugs now available for treating depression, anxiety and other mental disorders seem to do more good and less harm to patients than they did in the 1960s and 1970s - when chemicals like lithium were dished out with little or no regard for their damaging side effects like Parkinson's disease.

Although it's not at all clear how they all work, the drugs now available for treating depression, anxiety and other mental disorders seem to do more good and less harm to patients than they did in the 1960s and 1970s - when chemicals like lithium were dished out with little or no regard for their damaging side effects like Parkinson's disease.Here, the Serbian psychiatrist's advice on medication was clearly wrong (as was that of his predecessors), whereas the medication prescribed by all their successors worked much more effectively.

This raises a number of rather important questions.

If a psychiatrist gets a diagnosis wrong, what chance does a patient have of winning a case against him/her when it's on the official medical record that he/she was mad?

Would this patient have a viable legal case against the African and Serbian psychiatrists were he to make a formal complaint against them?

And what about Dr W?

On asking his new GP whether it was on his official medical record that he suffers from vascular dementia, she confirmed that it was.

She also confirmed that the psychiatrist who put it there was none other than Dr W.

But Dr W had never bothered to tell his patient this.

Last year, the DVLA medical group issued the patient with a new driving licence for a year - after

He did, however, tell the patient's wife that (a) he was suffering from vascular dementia (b) it's incurable and (c) as he'd steadily get worse, she'd better prepare herself for a progressively more dismal future for both of them (on the seriousness of vascular dementia, see below the line at the bottom of this page).

All he told his patient was that he would never be able to drive again and that he should dispose of his car as soon as possible - which he did.

Three years later, thanks his GPs and two more psychiatrists, Dr W's confident diagnosis turned out to have been utterly wrong.

With their encouragement, he wrote to the DVLA medical group, who issued him with a driving licence for one year n the first instance. They then extended it for another three years.

Meanwhile, consultants in psychiatry like Dr W continue to behave as if their specialism is based on as sound a knowledge base as treatments for eye, heart or brain surgery.

The big questions are how much damage are they doing and how many mental health patients are suffering as a result???

___________________________________________

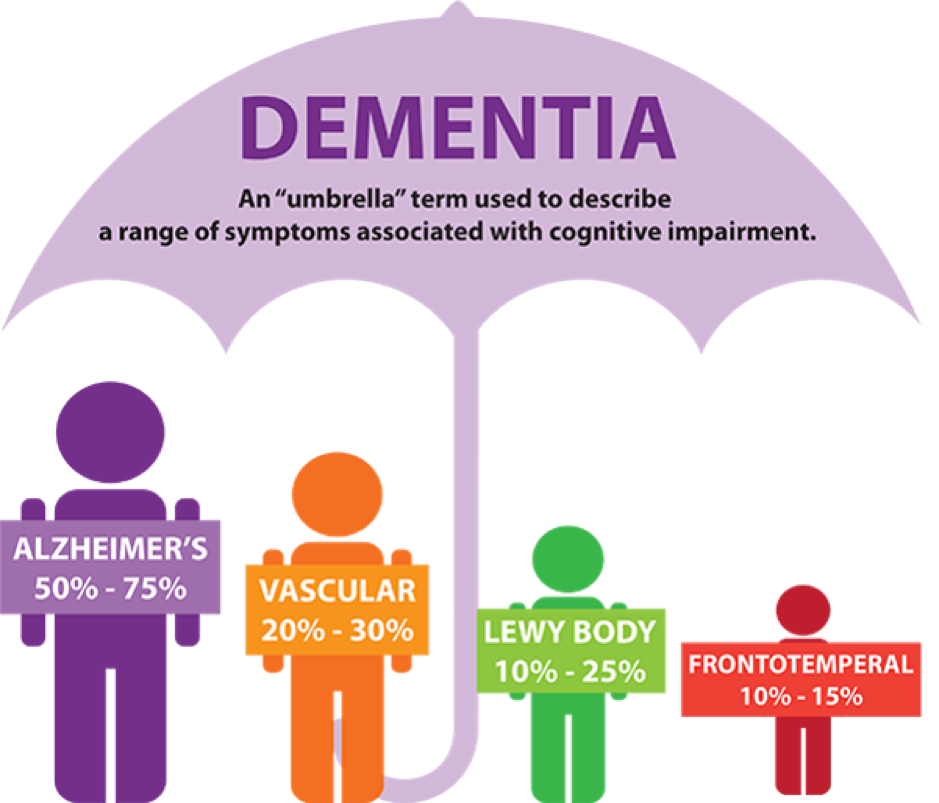

Types of Dementia

Dementia is a broad umbrella term used to describe a range of progressive neurological disorders. There are many different types of dementia and some people may present with a combination of types. Regardless of which type is diagnosed, each person will experience their dementia in their own unique way.

Vascular dementia is also known as “multi-infarct dementia” or “post-stroke dementia” and is the second most common cause of dementia.

Main symptoms:

Treatments or therapies: Vascular dementia cannot be cured, but people who have the ailment are treated to prevent further brain injury from the underlying cause of the ailment. Like Alzheimer’s disease, numerous medication and therapies may be used to help manage the symptoms.

Main symptoms:

- Memory loss

- Impaired judgment

- Decrease ability to plan

- Loss of motivation

Treatments or therapies: Vascular dementia cannot be cured, but people who have the ailment are treated to prevent further brain injury from the underlying cause of the ailment. Like Alzheimer’s disease, numerous medication and therapies may be used to help manage the symptoms.

No comments:

Post a Comment