In my continuously

failing efforts to tidy up my study, I came across a programme for a Royal Shakespeare

Company production of Julius Caesar at Stratford upon Avon in 1992 (below).

I'd forgotten that

the RSC had asked me to write a thousand-word article for it, in exchange for

which they gave me two free seats at an actual performance.

Reading it all these

years later, it struck me as better than I expected - and at least good enough to put on

my blog.

___________________________________________________

SHAKESPEARE AS SPEECHWRITER

… so little has the language of persuasion changed in

the last four hundred years that, were Shakespeare to return today, he would

have no trouble in marketing his services to contemporary politicians …

When it comes to writing

speeches to “stir men’s blood”, Shakespeare exhibits a mastery equal to that

found in the classical Roman times about which he was writing. For someone

living in an era when education was more or less synonymous with learning the classics,

it was hardly surprising that he had a good understanding of rhetoric. Perhaps

less obvious is the fact that the rhetorical techniques used by Mark Antony are

much the same as those used by today’s politicians in their attempts to win our

hearts and minds and votes.

Recent research, based on

analyses of video-recorded political speeches has examined sequences where

audiences applaud something said by a speaker. This makes it possible to

identify forms of language and modes of delivery that literally “move”

audiences to applaud what the speaker just said with a physical and audible

display of approval.

One of the main findings is

that about 75% of the bursts of applause during political speeches occurs after

the use of seven rhetorical devices, most of which feature prominently in the

Forum speech. For example, rhetorical questions come thick and fast. Even

before his first one, Mark Antony opens with one

there might be a case for giving praise where

praise was due.

An equally dramatic difference

in tone would have resulted had the second contrast had b of the simplest rhetorical devices, a list containing

three items: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen”. Famous examples from later

centuries include political slogans like “Liberté,

egalité, fraternité” and “Ein Volk, ein Reich,

ein Führer”

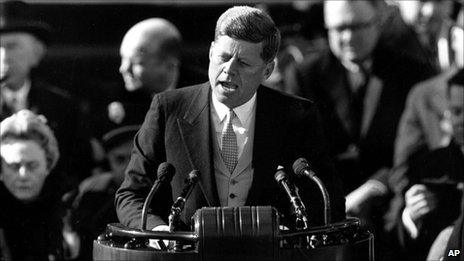

A more important device involves

the use of various forms of contrast, such as Margaret Thatcher’s “You turn

if you want to – the lady’s not for turning” and John F Kennedy’s “Ask

not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.”

Mark Antony launches into his speech with two consecutive contrasts: “I come

to bury Caesar, not to praise him” and “The evil that men do lives after

them. The good is oft interred with their bones.”

This early use of powerfully

formulated lines highlights the importance of both of striking an immediate

chord with an audience and of establishing the mood and agenda of what’s to

come. His opening is well crafted on each of these fronts and the structures

reveal a recognition of the importance of details like the order in which the

two parts of a contrast should be delivered. It is usually the second part with

which the audience will wish to affiliate or will highlight a theme for further

development – and this is exactly what happens here.

Think of the very different

expectations that would have been established if Shakespeare had inverted the

contrasts. Had the first one been “I come not to praise Caesar but to bury

him” it would have implied that the speaker was glad to see the back of him

and was about to tell us why, rather than hinting that een inverted too: “The

good men do is oft interred with their bones; the evil that men do lives after

them” would have suggested that we can forget about anything good Caesar

might have done and that what matters now is to clear up the mess caused by his

evil deeds.

Shakespeare therefore

constructed the sequence in just the right order for the mood and direction the

speech was to take. The way it develops then shows that contrasts are not only

useful for organising material on a line-by-line basis but can also provide a

single unifying theme for the overall structure of a speech. This is

illustrated by the recurring contrast between Mark Antony’s view of Caesar and

that of Brutus, summed up in the lines “I speak not to disprove that Brutus

spoke, But here I am to speak what I do know.” It also provides the

continuing leitmotif with his repeated references to what Brutus has

said about Caesar.

As one would expect from an

accomplished speechwriter, Shakespeare’s ability to combine different

rhetorical devices would have assured much prime-time news coverage for a

speaker using one of his scripts:

“I rather choose

“to

wrong the dead, to wrong myself and you,

“than I will wrong such honourable men”

is an example of a contrast in

which the first part involves a list of three. “you are not wood, you are

not stones, but men” has a third item that contrasts with the first two in

the list.

When it comes to content,

research has shown that the surest way to stir an audience is either to attack

your opponents or to praise your own side. On the evidence of the Forum speech,

this too is something Shakespeare understood, a Mark Antony heaps increasingly

praise on Caesar while using ironic praise of Brutus and his colleagues in an

implicit and thinly veiled attack on the opposition.

Another point to emerge from

research into contemporary speeches is that combining more than one rhetorical

device in a single sequence often produces a more enthusiastic response than

the use of a single device on its own. When that happens, such lines are very

likely to attract the attention of journalists, who may select them as

sound-bites for television news programmes.

When Mark Antony becomes

self-deprecating about his own skill as an orator, we hear a contradiction that

would have sounded amusing to those of Shakespeare’s contemporaries who were as

well-versed in rhetoric:

“I am no orator as Brutus is;

“But as you know me all, a plain blunt man…

“For

I have neither wit, nor words, nor worth.

“Action nor utterance nor the power of speech

“To stir men’s blood.”

With a contrast, alliteration

and two lists of three, he uses powerful rhetorical forms to deny his own

rhetorical ability!

As a speechwriter, then,

Shakespeare was a master of his craft. Indeed, so little has the language of

persuasion changed over the past four hundred years that, were he to return

today, he would certainly have no trouble in marketing his services to

contemporary politicians.

Less certain is which of our current

political parties would he help.

Max Atkinson is author of Our Masters' Voices: the language and body language of politics, Methuen, 1984.